The Wadden Sea region: a testing ground for climate adaptation

Introduction

Dutch people have a long history of adapting to water-based risks. In the last 1,500 years, at least 25 major floods have been recorded, some of which had profound impacts on the Netherlands coastline. Over the last few decades, Dutch thinking has evolved from a strong focus on controlling floods through ‘gray-only solutions’ toward living with water through solutions that are integrated or combined with natural systems and serve multiple functions for regional development. The nation is taking a proactive approach to climate adaptation, which is embedded in a long-term national policy framework.

The country has developed a layer of governance organized along hydrological boundaries, and an approach of sub sidiarity, which sees decisions taken at the lowest possible level. The OECD has recognized the excellent track record of Dutch water governance. The Delta Programme, which plans to 2050 with an outlook up to 2100 and has funding assured until 2034, is characterized by the search for ‘win-wins’ across climate adaptation, nature, and economic and social development. Several experiments that could potentially inform climate- adaptation work elsewhere are underway in the Wadden Sea region of the north-eastern Netherlands.

The Wadden Sea is an area of shallow water, wetlands, and mudflats that covers around 10,000 square kilometers along a 500-kilometer stretch of coast running from the north-western Netherlands into Germany and Denmark. Today its coastline is multi-functional. A Unesco World Heritage site, it is home to around 10,000 plant and animal species. It protects inland areas from coastal flooding and creates economic value for the region’s farmers in particular.

Thousands of years ago this coastline had wide salt marshes. Attracted by the fertile soil in low-lying coastal areas, humans began to settle despite the risk of flooding. They built their dwellings on top of mounds of loam, manure and garbage, known as terpen or wierden, up to eight by the flooding of surrounding land during a storm in 1916, and plans were finally approved in 1918 through the Zuiderzee Act. It set out the key objectives of protecting the central Netherlands against flooding, increasing Dutch food supply and improving water management. A dedicated governmental body was set up, the Dienst der Zuiderzee-werken (Zuiderzee Works Department), in May 1919. The legal arrangements ensured political commitment and budget allocation over a long time horizon.

The Afsluitdijk was a water management intervention on a scale the world had never seen before. Over the next four decades, around 1,650 square kilometers of fertile land were reclaimed from the Zuiderzee, and, initially, mostly given over to agriculture94. The Afsluitdijk was also, however, an ecological disaster, cutting off routes to fish spawning areas. Other large-scale infrastructure to reclaim land followed through the mid-20th century. At the time, the thinking was predominantly about water management, safety, and civil engineering.

Evolution in Dutch thinking on water management

![]() At national level, the Dutch government has a well-defined policy framework, governance structure, and predictable budget allocations for water-related infrastructure. Water governance in the Netherlands has historically reflected the principle of subsidiarity—taking decisions at the lowest possible level. The Netherlands has a separate meters above sea level. These mounds—early examples of adaptation to water challenges—date back to around 500 BC. Similar structures were built in Danish and German parts of the Wadden Sea region.

At national level, the Dutch government has a well-defined policy framework, governance structure, and predictable budget allocations for water-related infrastructure. Water governance in the Netherlands has historically reflected the principle of subsidiarity—taking decisions at the lowest possible level. The Netherlands has a separate meters above sea level. These mounds—early examples of adaptation to water challenges—date back to around 500 BC. Similar structures were built in Danish and German parts of the Wadden Sea region.

As human activity reshaped the landscape, storm surges increasingly breached the marshes. The first dikes may have been built as early as the first century AD. The rate of construction increased around the 12th century, with the founding of new small monastic orders. The 126 kilometer Westfriese omringdijkwas completed in 1250. Soon after, in 1287, St Lucia’s Flood claimed tens of thousands of lives and carved out the Zuiderzee, a shallow inland sea that stretches to around 5,000 square kilometers93. The city of Amsterdam grew to its south-west.

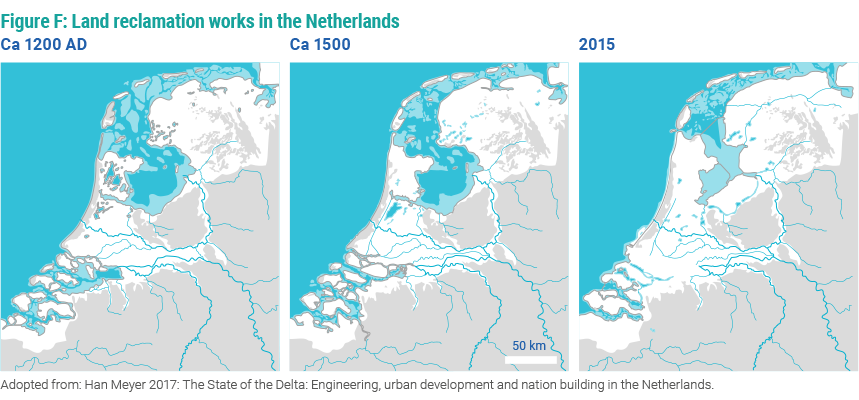

Over the centuries, kwelderwerken—land reclamation works—saw continuous reclamation of land from the Wadden Sea. Wooden dams were built out to sea, calming the waters so sediment would settle; over time, the sediment formed highly fertile land. The north-eastern Netherlands became known for its wealth, built on large- scale grain farming. Farmers had strong economic incentives to collaborate on constructing and maintaining dikes and polders.

Various proposals were made to close off the Zuiderzee. This would require the highly ambitious construction of a dam over 30 kilometers long, but it would also create opportunities to reclaim more land around the hundreds of kilometers of Zuiderzee coast, and turn the Zuiderzee into a freshwater store for farmers. The idea was given impetus layer of governance for the purpose of water management. Initially local ‘water boards’ were essentially associations of local stakeholders (farmers, landowners, politicians), but they gradually transformed during the 20th century into watershed-wide water management agencies with a board representing all stakeholders, including citizens, and their number decreased—for reasons of efficiency and govern- mental reform—from 3,500 in 1850 to 21 today. They form the fourth layer in the representative democracy of the Netherlands and have dedicated elections, as well as the right to levy local taxes. The Bureau voor den Waterstaat —the predecessor of the current Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management (Rijkswaterstaat)— was established in 1798 to coordinate the implementation of national-level projects.

Dutch thinking on how to live with water has evolved over the years—from ‘fighting against the sea’ toward living with water, from controlling floods toward ‘room for the river’— or, as so aptly put by the title of the Delta Commission’s 2008 report, Working Together with Water.

This transformation was driven by the growing understand- ing that it was proving impossible to predict and control nature, and the necessity not to respond to challenges of the past, but instead to prepare for those of the future, in a strategic and adaptive manner. While safety remains a key concern, increasingly a systems approach is being adopted. For instance, primary flood defenses—dikes—are combined with secondary-level defenses, such as open spaces that can serve as emergency reservoirs in case the dikes fail. Under normal circumstances, these provide space for recreation, grazing areas for cattle, and so on.

The focus has broadened to include spatial planning, a growing awareness of ecosystem and sustainability considerations, and the embrace of a ‘building with nature’ approach. The concepts of adaptivity and resilience are increasingly part of the national (policy) conversation. As climate change began to penetrate public awareness, there was strong popular support for forward thinking and proactive measures—with their long history of water-related natural disasters, the Dutch are increasingly aware of the risks.

The Delta program

![]() In 2012, the government passed the Delta Act, defined as a partnership between national, regional and local government and water authorities, based on the values of solidarity, flexibility, and sustainability. It created the position of Delta Programme Commissioner and a fixed, stand-alone Delta Fund. An average of €1.3 billion a year has been earmarked for this fund up to 2034, split around 50 percent for new investment and 50 percent for overheads, management and maintenance.

In 2012, the government passed the Delta Act, defined as a partnership between national, regional and local government and water authorities, based on the values of solidarity, flexibility, and sustainability. It created the position of Delta Programme Commissioner and a fixed, stand-alone Delta Fund. An average of €1.3 billion a year has been earmarked for this fund up to 2034, split around 50 percent for new investment and 50 percent for overheads, management and maintenance.

The Delta Programme Commissioner’s role includes advis- ing the government and promoting co-operation between national and regional branches of government and civil society. The Commissioner reports to the Minister of Infra- structure and Water Management, and participates in the Council for Financial Affairs, Economic Affairs, Infrastructure and Agriculture. Every year the Commissioner submits a proposal recommending new measures and reports on implementation, in consultation with a range of administrative bodies, private companies, and NGOs that are involved in designing, implementing, and maintaining infrastructure.

Water management is a long-term endeavor, so the pro- gram lays out plans until 2050, with a view to 2100. But it has not set out to give an immediate answer to the big question of the 21st century: given projected sea-level rises, should the Netherlands cease to invest in low-lying parts of the country, or invest whatever is necessary to keep those areas safe?

Instead, it takes an adaptive approach: every six years it asks the question of whether there are new developments or insights that warrant policy adjustments. This approach of keeping long-term options open has so far proved successful in gaining political support. However, it remains to be seen whether the program will be able to switch to a transformational strategy if needed.

Building with nature in the Wadden Sea region

Managing sediment has become a major struggle in the Wadden Sea region. The reclamation of land has narrowed gullies, which have also been deepened to serve as shipping routes. With fewer salt marshes and mud- flats for sediment to be deposited, waters have become more turbid, upsetting river and estuarine ecosystems. The imbalance between sediment and gullies also makes storm surges more of a problem: tidal and wind-driven flows can enter deep into estuaries, causing water levels to rise quickly and requiring the building of ever higher dikes.

The Delta Program includes strategies for seven regions in the Netherlands, including the Wadden Sea. The strategies reflect negotiation between different government agencies, citizens’ organizations, wilderness and nature conservation societies, industry and locals. The aim is to find win-win solutions that harness natural systems to improve coastal protection and deliver economic benefits.

The largest current project in the Wadden region is the reinforcement and renovation of the Afsluitdijk, which is scheduled to be completed in 2025. Since 1932, the Afsluitdijk has protected large parts of the Netherlands from flooding by the sea. The dam no longer satisfies current standards for water safety and so is due for renovation. In addition, greater amounts of water must be drained due to climate change. Rijkswaterstaat (the executive agency of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management) and the building consortium Level are working on strengthening and renovating it to protect the Netherlands against water in the future.

The dike is being reinforced by, among other things, giving the dam new revetment with specially developed concrete blocks: Levvel-blocs. The hinterland will be protected with new floodgates. The sluices will be reinforced and expanded with eight new sluices near Den Oever. Two pumping stations containing six gigantic pumps will be built. The sluices and pumps are required to drain surplus water from the IJsselmeer (Lake IJssel) to the Wadden Sea. A regional partnership entitled De Nieuwe Afsluitdijk is constructing a fish migration river near Kornwerderzand, which will wind its way through the Afsluitdijk. Migratory fish will be able to use the river to go back and forth between the Ijsselmeer (freshwater) and the Wadden Sea (saltwater).

Between the Afsluitdijk and the Eems-Dollard estuary— which marks the border with Germany—the Wadden Sea region is hosting a range of experimental interventions aimed at restoring sediment balance. These include:

![]() The ‘mud motor’ in Harlingen takes sediments dredged from the harbor and deposits them at sea, at a time and in a location where the tides will bring them back toward an area of coast where they can settle on salt marshes, bring- ing benefits for nature and coastal defenses.

The ‘mud motor’ in Harlingen takes sediments dredged from the harbor and deposits them at sea, at a time and in a location where the tides will bring them back toward an area of coast where they can settle on salt marshes, bring- ing benefits for nature and coastal defenses.

![]() The Brede Groene Dijk (Wide Green Dike) is taking naturally deposited mud from the harbor approach channel and a nature area and ‘ripening’ it into clay by drying and desalinating it, then using it as a building material to reinforce the dike. A one-kilometer stretch is expected to be completed in 2022.

The Brede Groene Dijk (Wide Green Dike) is taking naturally deposited mud from the harbor approach channel and a nature area and ‘ripening’ it into clay by drying and desalinating it, then using it as a building material to reinforce the dike. A one-kilometer stretch is expected to be completed in 2022.

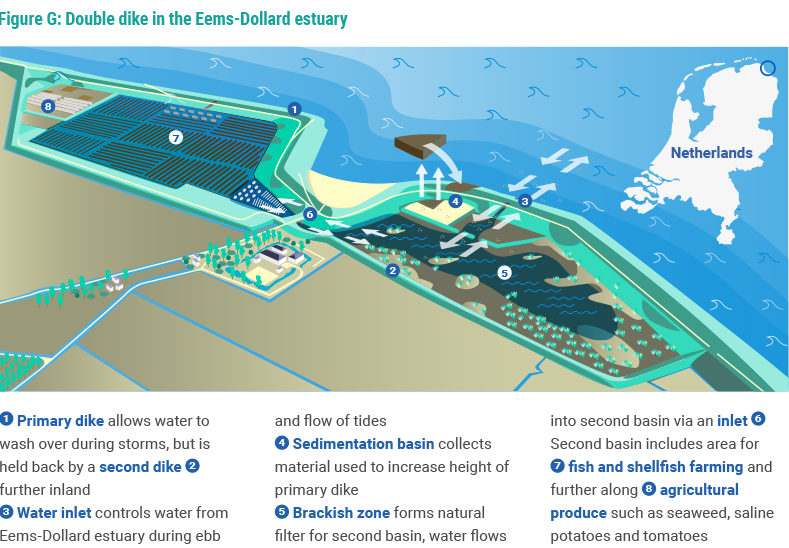

![]() The ‘double dike’ in the Eems-Dollard estuary involves constructing a second dike behind one that protects from the sea—a more cost-effective alternative to strengthening the sea-facing dike. A 27-hectare area between the two dikes will be used for farming crustaceans, shellfish, and salt-tolerant crops, as well as enabling sediments.

The ‘double dike’ in the Eems-Dollard estuary involves constructing a second dike behind one that protects from the sea—a more cost-effective alternative to strengthening the sea-facing dike. A 27-hectare area between the two dikes will be used for farming crustaceans, shellfish, and salt-tolerant crops, as well as enabling sediments.

Conclusion: The importance of subsidiarity and broad-based public support

![]() Changing estuarine dynamics is an expensive, multi-decade undertaking that requires budget predictability, a dedicated legal framework, and appropriate governance structures organized on water-based principles—the Netherlands’ water boards being a case in point. In the Netherlands, long-term water management has risen above party politics and has broad-based public support. A proactive stance on climate-change adaptation— looking forward, rather than waiting for disaster to become imminent—has emerged as a non-partisan issue that commands support through the entire Dutch society.

Changing estuarine dynamics is an expensive, multi-decade undertaking that requires budget predictability, a dedicated legal framework, and appropriate governance structures organized on water-based principles—the Netherlands’ water boards being a case in point. In the Netherlands, long-term water management has risen above party politics and has broad-based public support. A proactive stance on climate-change adaptation— looking forward, rather than waiting for disaster to become imminent—has emerged as a non-partisan issue that commands support through the entire Dutch society.

Over recent decades, the Netherlands has seen a broadening from primarily focusing on prevention and control of floods toward living with water and deploying a combination of gray and green infrastructure. Combined with a deep understanding of the Dutch Deltas, this has allowed the Netherlands to look for innovative win-win solutions that benefit ecology, economic development, and human wellbeing.

The country’s experience also shows that effective action is most likely when different levels of government work together effectively, following the principle of subsidiarity in decision-making—from local-level solutions owned by citizens to the involvement of national government when needed to finance innovations and scale. The restoration of the Afsluitdijk exemplifies how discussions between different stakeholders can lead to a consensus on necessary action.

Trending Discussions

From around the site...

“Absolutely interested! I'll connect via email to discuss reviewing and enhancing the Economic Analysis of Climate...”

Adaptation-related events at COP28 (all available to follow/stream online)

“Please check out these adaptation-related events taking place at COP28 - all available online (some in person too if...”

Shining a light for biodiversity – four perspectives to the life that sustains us. Four hybrid sessions.

“30 November to 19 December 2023 - Four Sessions Introduction The SDC Cluster Green is happy to invite you to the...”